Treatonomics Is Bigger than a Recession Cycle. It's a Cultural Shift

Why the lipstick effect no longer explains what’s happening.

For years, rising spending on “little treats” has been explained with a familiar idea: the lipstick effect. When times are hard, people cut back on big luxuries and reach for smaller indulgences instead.

That explanation used to work, but it doesn’t anymore. As we look ahead to 2026, treatonomics is emerging as one of the most important consumer and marketing trends to understand.

Today’s treat economy isn’t behaving like a cyclical response to recession. It’s broader, more persistent, and showing up across industries, demographics, and regions. What looks like a simple indulgence is better understood as an adaptation. A rational response to a world where uncertainty is prolonged, traditional milestones are slipping, and systems increasingly reward immediacy over patience.

Look more closely, and it becomes clear that treatonomics isn’t a cyclical downturn pattern, but a cultural shift shaped by a rare convergence of forces.

Table of Contents

What is The Lipstick Effect?

The “lipstick effect,” or the “lipstick index,” is an economic theory that posits that during periods of economic recession or uncertainty, consumers will forgo big-ticket luxury items (such as expensive cars or vacations) in favor of smaller, affordable indulgences like premium lipstick. These purchases serve as a “pick-me-up,” providing emotional reassurance and a sense of control when financial circumstances feel unstable.

The term was coined by Leonard Lauder, the chairman of The Estée Lauder Companies, following the 2001 recession in the United States. Lauder observed an 11% spike in lipstick sales in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, noting that, "When things get tough, women buy lipstick".1

“In stressful times, many consumers are reaching out for those small indulgences that provide momentary pleasure.” – Leonard Lauder

While Lauder solidified the term in the modern lexicon, the "lipstick effect" has been observed during several distinct periods of economic turmoil over the last century.

The Great Depression (1930s): While the term was coined later, the phenomenon was first notably documented during the Great Depression. Despite plummeting industrial production, sales of cosmetics reportedly increased by as much as 25% during this era.2 Women utilized affordable luxuries like lipstick to maintain social poise and morale during a time of severe financial strain.

9/11 and the 2001 Recession: The concept was formally named and popularized by Leonard Lauder, but Estée Lauder wasn’t the only cosmetics company to observe significant sales growth during this time. The demand was so high during this period that Mac Cosmetics factories reportedly added extra shifts to keep up with production.3

The Great Recession (2007–2009): During the 2008 financial crisis, the phenomenon persisted but shifted product categories. While lipstick sales rose for some companies, nail polish emerged as the dominant affordable luxury, with sales increasing by 65%.4 This shift led some to refer to nail polish as the "new lipstick" of that recession. Research covering this period indicates that women engaged in a psychological substitution, significantly reducing expenditures on clothing while increasing spending on cosmetics to "treat" themselves frugally.5

The COVID-19 Pandemic (2020–2022): The pandemic disrupted the traditional lipstick effect due to the widespread mandate of face masks, which caused lipstick sales to fall. However, the desire for small luxuries remained, shifting toward eye makeup (dubbed the “Mascara Index”), skincare, and fragrances.6 Consumers utilized these purchases as “retail therapy” to cope with the lack of control and uncertainty characterizing the lockdowns.7

The Modern Era: "Treatonomics" (2022–?) In the current economic climate, the lipstick effect has evolved into "treatonomics" or "little treat culture," described by many as the lipstick effect on steroids. But, as we’ll see in the next section, this modern iteration is a very different beast.

Why Treatonomics Is So Much Bigger than the Lipstick Effect

The lipstick effect explains what people do during periods of financial stress but it doesn’t fully explain treatonomics. What we’re seeing now isn’t a simple consumer behavior pattern. It’s the result of five different forces converging, reshaping how people think about the future, how culture spreads, and how easily markets can respond to emotional demand.

1. Record Uncertainty Is Threatening Trust in the Future

Economic uncertainty used to arrive in waves, but lately it feels ambient.

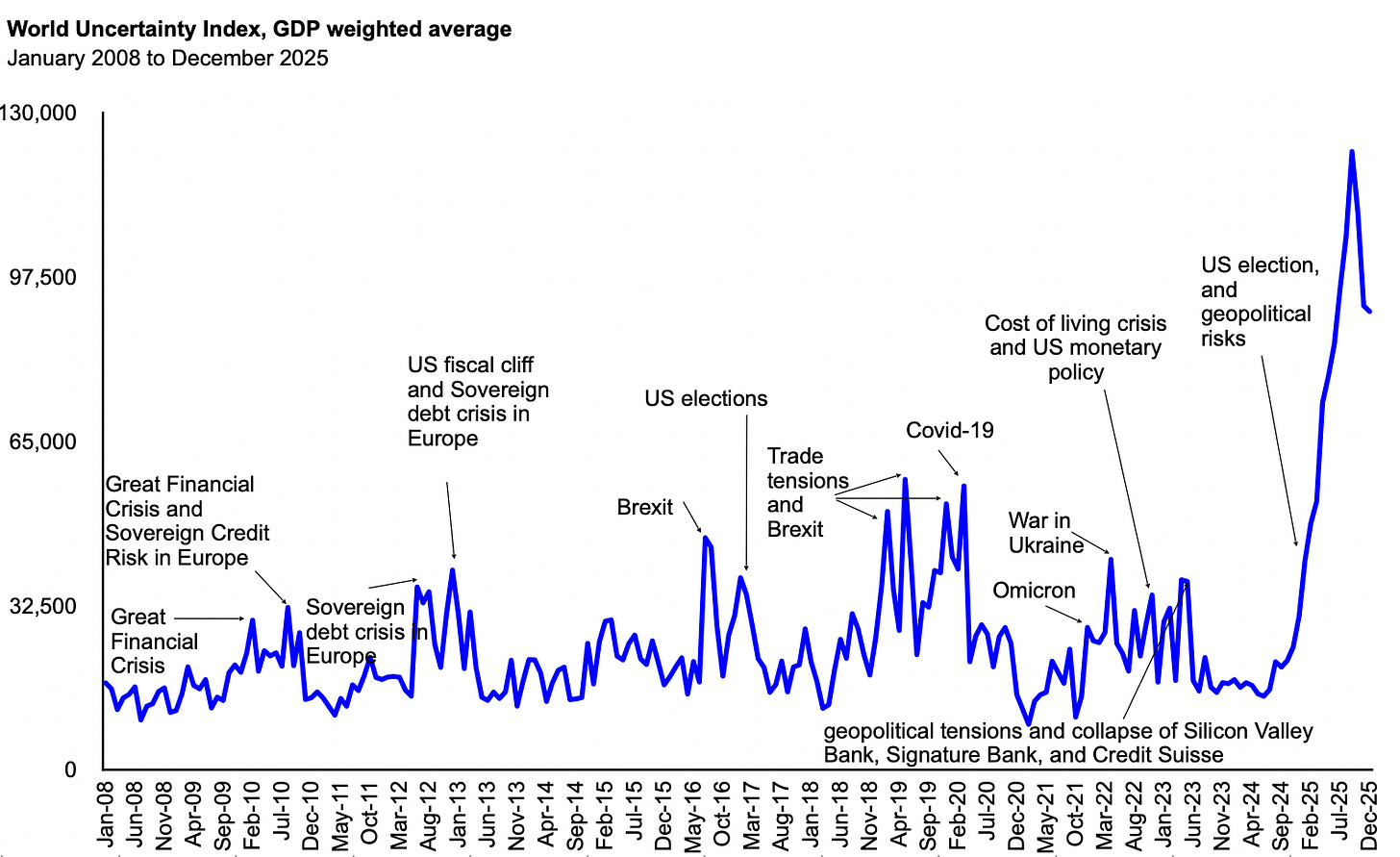

Measures like the World Uncertainty Index remain elevated well beyond traditional recessionary windows, reflecting not just financial volatility but also political instability, climate risk, geopolitical tension, and rapid technological change.

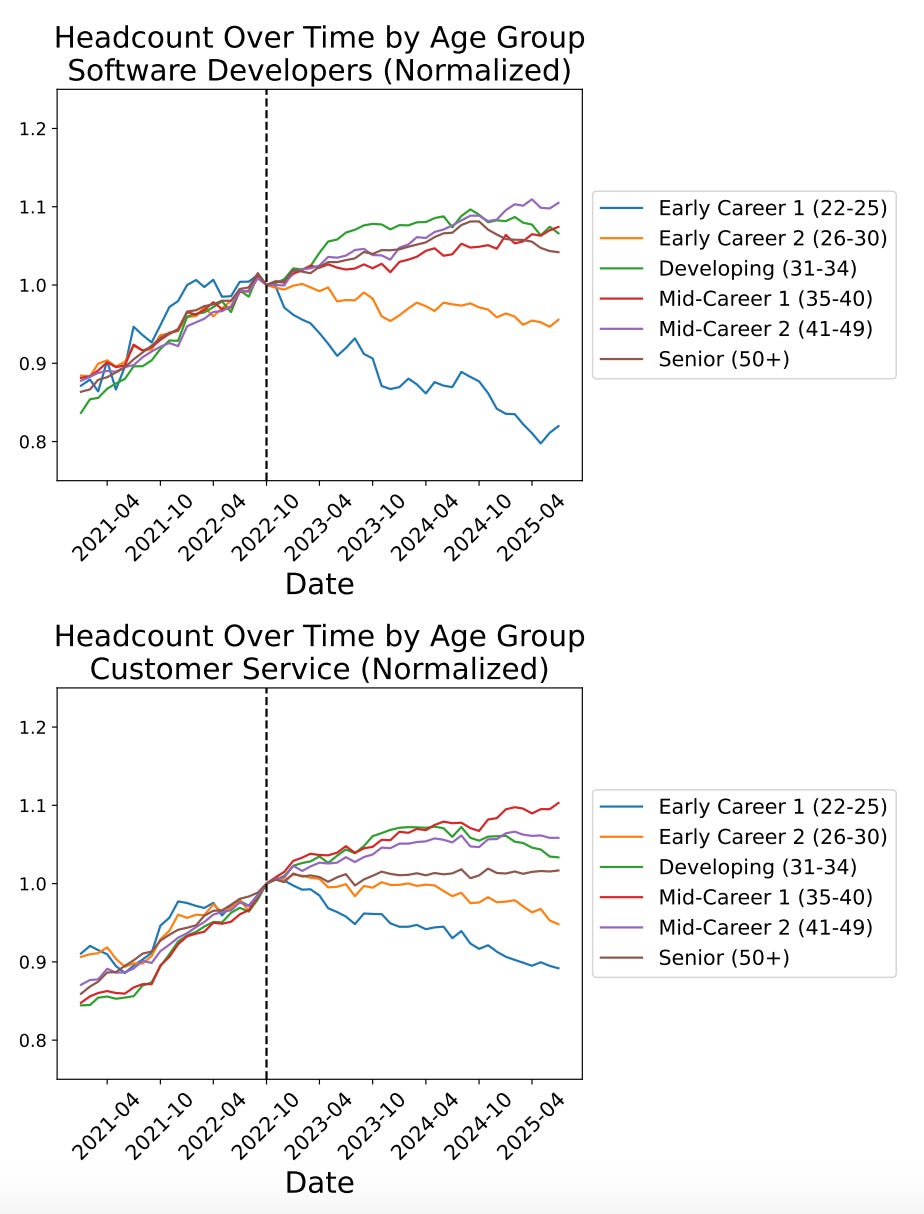

Increasingly, that uncertainty is felt in the workplace as AI reshapes which roles are stable, transitional, or at risk.

Recent research using high-frequency payroll data shows that early-career workers in the most AI-exposed occupations have already experienced meaningful employment declines, even as more experienced workers in the same roles remain relatively insulated.8 The adjustment is happening through jobs not materializing, rather than wages simply falling, reinforcing the sense that traditional career on-ramps are becoming less reliable.

Both entry-level technical roles and lower-paid support roles are seeing declines, while more experienced workers remain comparatively protected.

That kind of signal travels far beyond the people directly affected. It makes long-term planning feel harder to model, and career progress feel more conditional. When the future looks opaque, delayed gratification starts to feel speculative rather than virtuous.

Consumer behavior is deeply tied to time horizons. When people trust the future, they tolerate friction in the present: saving, optimizing, committing to long arcs of effort. But when that trust erodes, present-oriented decisions become more rational and immediate comfort starts to outperform hypothetical payoff.

Treatonomics thrives in short time horizons because the payoff is immediate.

2. Traditional Milestones Are Slipping Out of Reach

For decades, delayed gratification made sense because the milestones were visible and achievable: buy a home, build equity, advance steadily in a career, unlock stability.

But for many people, these milestones are slipping out of reach.

In the US, the median age for first-time homebuyers, which to rose to 40 last year, is getting older faster than we age. The year before it was 38, and the year before that it was 35. How can a young person expect to reach a milestone when it moves farther away each year?

When big milestones stop functioning as reliable markers of progress, people don’t stop wanting progress so they shrink the unit of measure in response.

This is where inchstones come in.

What Are Inchstones?

Inchstones are small, self-defined milestones or micro-achievements that consumers celebrate in place of traditional, major life goals like marriage, parenthood, or homeownership.

As economic volatility and the rising cost of living make “ordinary” adult milestones increasingly unattainable (or undesirable), many people are redefining what constitutes a celebratory moment. Rather than saving for distant goals, they use inchstones to inject optimism and a sense of control into their lives.

Inchstones often mark events that were historically not celebrated (or sometimes even viewed negatively).

Celebrating the conclusion of a big project at work with a new piece of jewellery.

Throwing an "I quit my job" party and buying a new outfit for it.

Buying a new collectible LEGO set as a reward for leaving a bad relationship.

Treating yourself to an expensive beverage for getting through the week.

Inchstones also serve as a trigger for treatonomics, by providing a reason to spend disposable income on immediate happiness rather than long-term savings.

This doesn’t mean people have abandoned long-term goals, but many are navigating a reality in which the path to those goals feels less stable, and waiting for distant payoffs without intermediate signals is emotionally unsustainable.

3. Social Media Turned One-Off Treats Into Lasting Culture

If uncertainty created the demand for little treats, social media made it contagious.

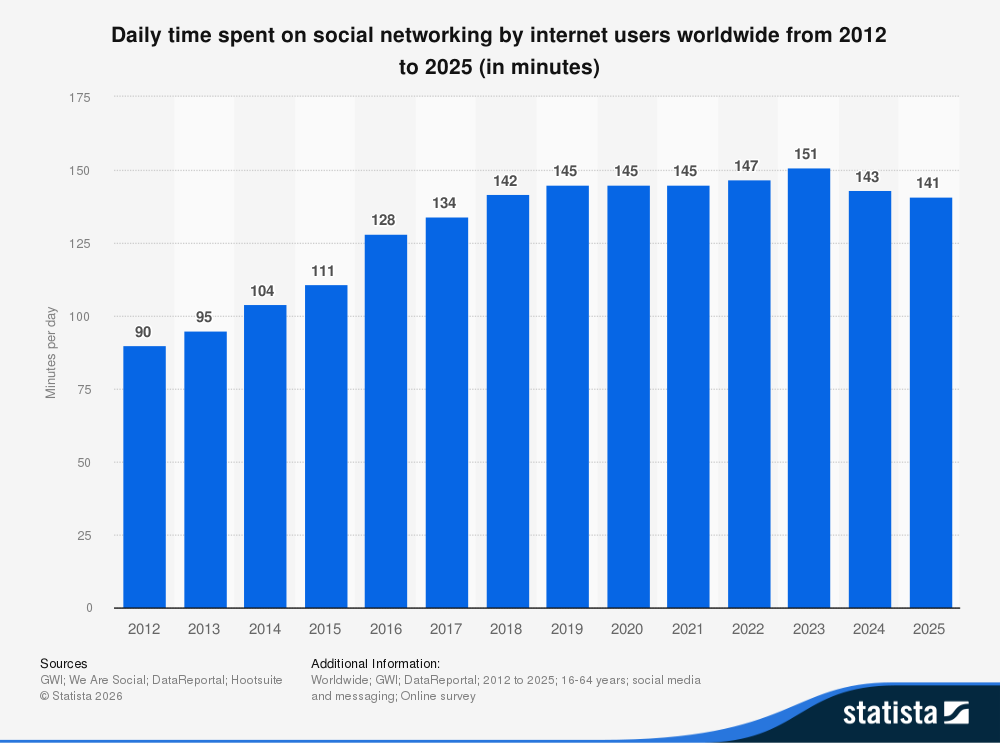

Endless scrolling and algorithm-driven feeds are designed to keep users engaged by delivering unpredictable, novel content that triggers brain reward pathways. It’s no surprise that, for the last several years, the average person spent nearly 2.5 hours on social media every day.

Research on “infinite scroll” interfaces shows they can function much like compulsion loops, exploiting our brain’s reward mechanisms and encouraging repeated engagement, and studies have connected this pattern to dopamine-related reinforcement and increased social comparison on social platforms.9

Hashtags like #littletreatculture turned private coping into a shared ritual. We already know from the lipstick effect that small luxuries restore a sense of control under stress, but social media made that behavior visible. Little treats have become something you can post, recognize, and repeat. These posts do more than reflect behavior; they spread it. One person’s performative joy became another’s ambition, not as a distant aspiration, but as something immediately within reach.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

4. Direct-to-Consumer and Flexible Manufacturing Let Brands Respond Rapidly

Treatonomics extends beyond the lipstick effect because it’s not merely demand-driven; it is production-enabled. In earlier downturns, shifts toward small luxuries emerged despite significant supply-side constraints. Today, those constraints have largely been dismantled. Flexible manufacturing, lower minimum order quantities, and direct-to-consumer models allow brands to respond to micro-demand with unprecedented speed, translating fleeting emotional impulses into viable products.

This fundamentally changes what the market can support. Brands no longer need to underwrite long-term, broadly appealing demand to justify production. Instead, they can test narrowly defined ideas, iterate quickly, and respond to cultural signals as they emerge—often while the underlying emotional need is still forming.

This is a critical difference. In the past, not every urge could become a product. Now, almost any urge can. Markets can meet micro-desires with speed and precision, reinforcing treat-oriented behavior and allowing it to persist at scale rather than appear only in moments of stress.

5. Distribution and Payment Infrastructure Removed the Final Friction

Finally, the financial and distribution layers have been optimized for action.

The rise of social commerce has collapsed discovery, purchase, and payment into a single flow. Platforms like TikTok no longer merely surface desire; they help people act on it. With TikTok Shop (which sold $33 billion in 202410), the same app that introduces a product also hosts the checkout. With #littletreatculture, the marketing funnel has collapsed in on itself, and awareness, interest, decision, and action can all happen within seconds of each other.

Buy-now-pay-later options (like Klarna) complete this shift by decoupling purchase decisions from immediate liquidity. By spreading the cost of small purchases over time, BNPL reframes treats as low-stakes commitments rather than discrete financial tradeoffs. The emotional payoff is immediate, while the cost is deferred and psychologically softened.

Together, social commerce and BNPL lower the threshold for action. Present-oriented spending scales not because consumers are less disciplined, but because the system increasingly removes the moments where discipline once thrived.

What Treatonomics Signals for the Decade Ahead

The unique rise of treatonomics signals a profound, long-term structural shift in the global economy for the decade ahead, moving away from a focus on future security toward a priority of “present wellbeing” and emotional regulation.